Inchoate

The doctor waved her hand through the air between us. A fly kept darting in and out of our conversation. “Avoiding stimulants can help with symptoms in the short term.” She paused, studying my face, her Ivy League credentials mounted on the wall behind her. “Caffeine, nicotine. Alcohol, too, because of how it interacts with the central nervous system. Really anything that can cause excitation in these parts of the brain.” She tapped the screen next to her, where the inside of my skull softly glowed in black and white. The end of her pen tick-tick-ticked an oblong blob at the base of my cerebellum. The blob was wedged down into the top of my spinal canal, competing for space with my spinal cord.

I rubbed the back of my neck and nodded. The muscles were tight, as always.

“So, is there anything I can do, like, preventatively…to help ward off the chances of…” I searched for a way to finish the sentence without including the words “ending up in a wheelchair.” Nothing came to mind. I trailed off, but it didn’t matter. She knew what I was saying.

“Nothing that will impact its progression.” Sympathetic smile. “But here’s the good news: You have a front row seat to your symptoms. So, if this progresses, you’ll be the first to know. And, if symptoms do worsen, which they may or may not, you can make the decision on whether to pursue intervention when the time comes.”

Intervention, in this case, was a sanitized stand-in for “invasive brain surgery”.

I smiled and thanked her for her time. As I left the doctor’s office, walking out into a drizzly Seattle afternoon, my peripheral vision danced, mildly, each time I scanned my surroundings.

Ω

Sometimes I hardly notice it. Other times it causes me low-grade nausea. And when one of my condition’s trademark headaches clamps down, it can be all I can do to keep my eyes open. This vision issue is what I’d made the appointment for. Nystagmus. Essentially, it’s when your eyes have a hard time lining up. It can cause double vision, or this sort of, buzzing sensation. My case isn’t bad, but it’s steadily progressed over the past decade, or so. And, unfortunately, as with the rest of my symptoms, there’s really only one intervention.

Columbia Tower, Seattle, WA.

Despite the rain, I’d parked at the top of the parking garage so I could glimpse the Seattle skyline, which I only see a handful of times each year when I’m on the west side of the state. I live in eastern Washington, in the rain shadow of the Cascades, where the western evergreens give way to sagebrush and grasslands.

I reached my Jeep, settling into the driver’s seat, and popped the tab on the energy drink sitting in the console. I took a long drink, closed my eyes, leaning my head back against the headrest. I had an hour-plus of rainy I-5 traffic ahead of me. I was heading south to Puyallup that afternoon, to drink hard cider and play trivia with one of my closest friends.

I thought of the doctor’s advice about avoiding caffeine and alcohol. Nicotine, too, but that wasn’t an issue for me. I don’t like it’s sensory effects, so outside of a couple-dozen drunken cigarettes on dive bar patios over the years, I don’t use nicotine. But caffeine and alcohol? Lifestyle staples.

Opening my eyes, I stared at the towering Columbia Center that loomed over the city that surrounded it, its black windows seeming to inhale the gray-sky backdrop. My eyes moved to the left, spotting the famous Ferris wheel down on the boardwalk. As I stared at it I realized I had clenched my right eye shut, so as to eliminate the mild double vision when I attempted to look at it with both eyes open.

I sighed, closing my eyes again, and took another drink.

View of the Columbia River from the Wild Horses Monument, Vantage, WA.

Nystagmus is just one of the symptoms of this condition I have. The brain one the doctor had tapped her screen about.

Chances are, you’ve never heard of it. If you have, it was likely in passing, or maybe you have a friend, or a friend of a friend, who has it—or had it—or maybe you heard Hugh Laurie diagnose a patient with it on that one episode of House you saw some 15 years ago. Maybe you know it’s this…well, you’re not really sure how to explain what it is, or what exactly it does to a person, but you’re pretty sure it has something to do with the brain.

It’s called Chiari Malformation. It’s not something I caught, it’s not something that developed as a consequence of poor life choices (although, there’s been plenty of those), and it’s not something that developed as a result of years of ingesting microplastics, or years of drinking well-water rich in nitrates, or a lifetime riddled with processed foods.

I was born with it.

My dad has it, and chances are his dad, or one of his elders, had it, and so on, and he passed it down to me and my sister. He didn’t choose this, nor did he make a conscious decision to have children in spite of having the condition, given he didn’t know his own brain was malformed until he was forty years old and, in under a year’s time, had nearly lost complete use of his left arm due to rapid onset atrophy.

I don’t want to dive into some deep, dry explanation of what Chiari is exactly, so here’s the quick and dirty downlow that is maybe-probably not 100% accurate, but close enough:

Chiari is where the ass-end of your cerebellum has grown a little frog tail that a cerebellum shouldn’t have (sort of like Jason Alexander’s tail in Shallow Hal, but inside the back of your skull). It’s got nowhere else to go but down your spinal canal, and now your spinal cord is having to compete with this little frog tail for elbow room, and your brain juices that flow up and down your spinal canal and into your brain aren’t flowing quite as…flowingly, and since there’s this lack of flowinglyness, and there’s pressure being applied where it shouldn’t be, and since this is the part of your brain that handles coordination and your muscles and motor function and all that stuff…your shit is getting all fucked up by the goddamn frog tail.

(If you’re interested in a more accurate and scientific explanation, or one with fewer expletives and references to problematic turn-of-the-century rom-com’s, please feel free to ask Google, Bing, or *swallows frog in throat* ChatGPT.)

Keeping to my promise of not turning this into a dry, clinical dissertation on Chiari (I’m far too ignorant and unqualified to give one, anyway), I’ll just reiterate what I mentioned earlier. For someone in my situation, there’s really only one intervention for the condition, and, of course, that’s good ‘ol invasive brain surgery.

One can, of course, load up on painkillers to dampen the pain, or turn to herbal, natural, or holistic remedies. There are lifestyle choices that can help, too, such as staying in good physical health, maintaining ample mobility of the muscles and joints, avoiding things like too much overhead lifting, and avoiding heavy coughing fits (there were a few bong rips I took in college that likely did me no favors). There are little things, too, like not riding (stupid fucking) rollercoasters, or anything that spins or jerks around too fast. Also, and this is a big one: Avoiding being punched in the back of the head.

And, like Doc said, it wouldn’t hurt to take it easy on the energy drinks in the morning, and the whiskeys and wines and beers and hard ciders in the evening.

But these, of course, are not treating the root cause of the symptoms. They’re treating, and attempting to mitigate, the symptoms themselves. Symptoms like Chiari headaches, which are not the same as migraines, or tension headaches, but are their own special kind of hell, with nausea-inducing, throbbing pain that radiates from the back of your skull, wraps it’s electrical tentacles up and around your dome, and can pulse through your entire body. My Chiari headaches are child’s play compared to some Chiari patients’, and my worst Chiari headaches are the most severe physical pain I’ve ever endured. At their best, they can make it really hard to enjoy life, and at their worst, they can be completely debilitating, to the point of blacking out altogether.

There are other potential symptoms, of course, a list far too long for the purposes of this essay. But a shortlist of what I’ve dealt with to varying degrees are issues like the aforementioned Chiari headaches, poor balance, nystagmus, trouble breathing properly (including sleep apnea), hormone imbalances, and ever-present muscle pain, knots, and spasms in my neck, shoulders, and back.

(And, to be clear, I know that I have it good. Really good, compared to so many people with Chiari. And I’m truly grateful for that, despite all the whining I’m doing here.)

Getting back to the point, as far as treating the root cause of all those symptoms, the only option is brain surgery. And this particular brain surgery consists of opening up the back of your skull and literally cutting out as much of the malformation (the frog tail…) as they can, in order to alleviate the pressure it’s causing, and, hopefully, stop it from continuing to fuck your shit up. It’s called decompression surgery.

All to say, that puts someone like myself, and others like me, in a bit of a conundrum: Monitor, treat, and mitigate your symptoms, and wait and see if-and-when your condition worsens, and, when the time comes, consider surgery. Given the inherent risks with any major surgery, let alone operating on the literal control center of your entire body, the exact “when” in “when the time comes”, is entirely, impossibly, helplessly subjective. Basically, it’s when the risks of surgery no longer outweigh the impact the symptoms are having on your life.

Some people get lucky. Their symptoms never reach the point of necessitating surgery. Some, surely, have Chiari and never even know it, living in blissful, mostly painless ignorance of the ticking time bomb in their brain that, thankfully, never went off.

Others end up in wheelchairs. Some end up paralyzed. Some die. And it’s fickle. When it may clamp down on someone, when it may cause major, severe problems for them, is largely impossible to predict. It feels infuriatingly random, arbitrary. Uncertainty incarnate.

Some of the unlucky people end up like my dad.

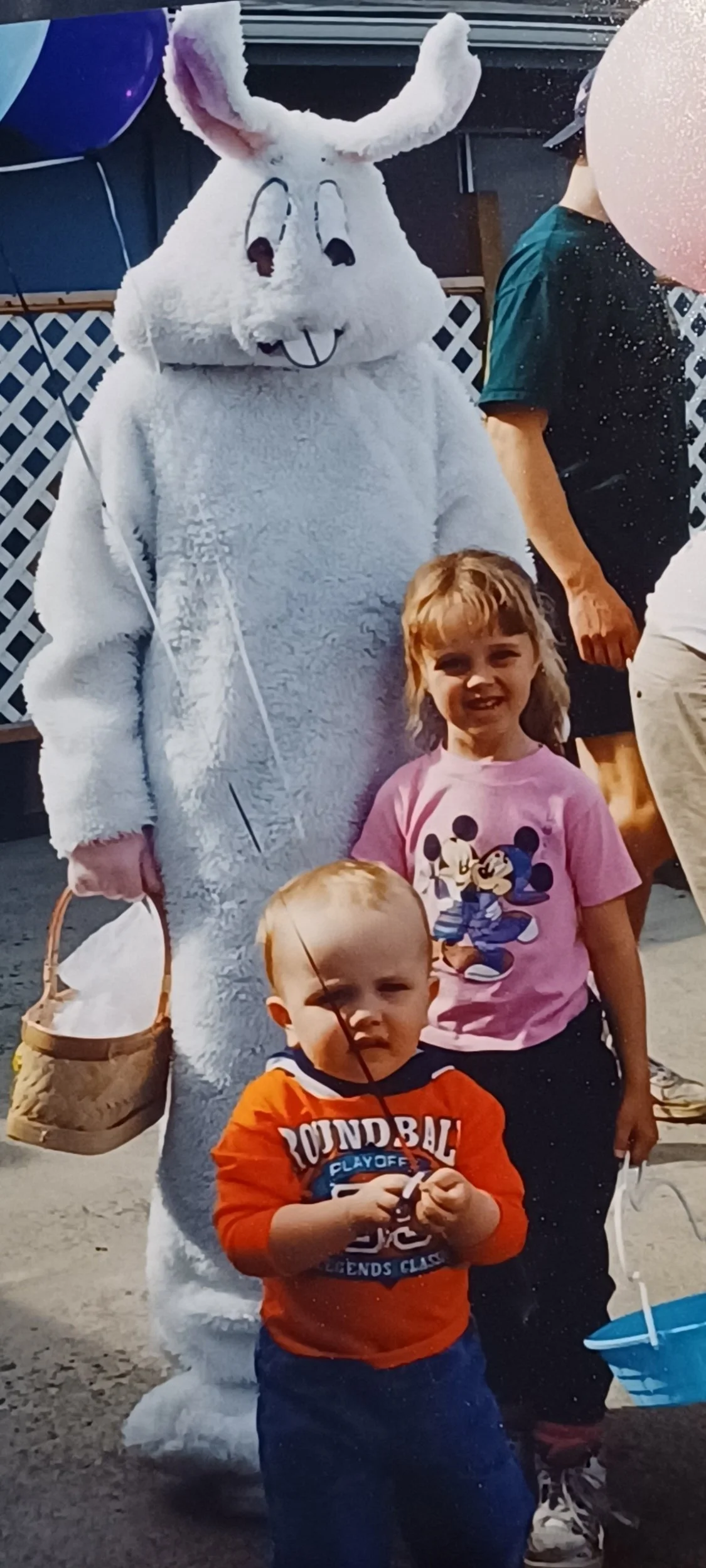

My older sister, Lacey, and I hanging out with a super creepy Easter bunny.

I first became familiar with the word Chiari when I was about 8 years-old. That’s around the time my larger-than-life-in-my-eyes father was diagnosed with this rare neurological condition. His diagnosis came after years of severe and worsening headaches, back problems, and eventually, rapid atrophy in his left arm that nearly left it paralyzed. While I knew something big was happening, there was no way I could understand at the time just how instrumental this would become in all of our lives. The knowledge of his diagnosis, and everything that came with it, was information I didn’t know what to do with in my 8 year-old mind.

To that point, I’d known my dad as a man who worked long weeks as a “Teamster” at some place called “Hanford”, wearing work boots, button-downs, jeans, and sweat-stained trucker hats. When he wasn’t at work driving semi’s weighted down with containers of hazardous nuclear waste, or moving office furniture from one building to another, or waking up at midnight to do snow removal for the rest of the several thousand employees on the nuclear reservation, or any of the other back-breaking tasks he did as a Teamster, he was usually working on something at home. Like growing a garden with Mom, or tackling some home improvement project on the old farm house we rented that never ran out of things to fix. He was throwing batting practice for my sister and I in the yard, or he and Mom were taking us camping, or to lunch at the park on Mom’s work break. In short, he was being a great dad. This is something he never stopped doing, but his diagnosis, and his—and our, as a family—journey with Chiari, completely upended the balance of everything in our world. Nothing would ever be the same.

I felt on the periphery of all of this, and could only understand so much of what was happening. Sure, Mom and Dad explained it to me and my big sister, and I could regurgitate some of what I was told, but in retrospect, I don’t think I really had a firm grasp on what exactly Chiari was until I was in my early twenties. Before that, and even in the time since, I tend to hold it at arm’s length. Most of the time I’m able to seamlessly compartmentalize its existence, and forget what’s going on in my own brain.

When I was 13 years-old I had my first MRI, and discovered that not only did I also have Chiari, but that my herniation (frog tail…) was roughly three times longer than that of my dad’s. My dad, who, in those intervening five years from 8 to 13, had gone through hell. Physically, emotionally, spiritually, all of it. And, in the orbit of that, our whole family had gone through hell alongside him. As a result, many of my childhood memories, particularly in those late elementary and early middle school years, are occasionally fuzzy, a little unclear, and sometimes disordered. I believe it was this period of my life when I first learned to compartmentalize, to disappear into my own imagination, my own stories, narratives, in an effort to bring some semblance of order, some sense of control, over what was happening around me, because what was happening around me was too unpredictable, too chaotic, too filled with anger and bitterness to stare at for too long, to hold in my 13 year-old mind.

At that time, my symptoms were relatively mild. I had hormonal imbalances, and I had balance…imbalances (I wasn’t super coordinated and would get dizzy easily—I still do (again, fuck rollercoasters)), and I was already getting the occasional Chiari headache, but for the most part, I was a pretty normal kid. Chubby, shy, and awkward, crushing on girls I was too afraid to talk to, and obsessed with sports I was never much good at.

So, much like the knowledge of my dad’s diagnosis, I didn’t really know what to do with the knowledge of my own diagnosis, and rather than diving in and learning about my condition, or growing worried and paranoid about it, I gravitated toward compartmentalization and distraction. I buried it deep down, and I didn’t really talk, or even think about it, all that much.

Of my four family members—Mom, Dad, and my big sister, Lacey, who also has a Chiari malformation—I guarantee I know the least about this condition that has derailed all of our lives in its own way. Despite my attempts to avoid looking it too closely in the face, I can confidently say that my dad’s and my family’s journey with Chiari was not only a defining feature, but the defining feature, of my childhood.

If my dad’s brain had just been normal, and if my brain, and my sister’s brain, were just normal, everything, everything, would have been, and would be, monumentally different. Better? At least in some ways. And while I fundamentally do not believe in our culture’s predominant ideas around the existence of free will (conversation for another day), I can’t help but wonder what things would have been like, what things would be like, if this condition hadn’t come into our lives.

And that knowledge, that train of thought, is something I’m not sure what to do with, either.

I try not to think about it.

My dad was 32 years-old when I was born, a year younger than I am today. My thoughts about having children have shifted over the years, but as I get older, the more I want to be a father. Despite my shortcomings, of which I could identify a long list, I also believe I might make a good dad. I like the idea of watching this strange amalgamation of me and my partner coming into being. Of walking through a pasture or along a hiking trail with them and struggling to answer their questions. Of watching them skin their knees trying to get over that log, or encouraging them to figure something out for themselves. Watching them learn and grow. Reading them a story as they fall asleep next to me. Trying to get them excited about the things that excite me, only to watch them get excited about something else entirely, and in turn, learning to find excitement in those things myself. Or, at least, getting really good at pretending to be excited about whatever they’re into (Mom and Dad, thank you for the hundreds of hours you spent listening to me talk about completely made up football and baseball and basketball teams over the years).

I don’t know if these sound like shallow reasons for wanting to be a dad, but this desire I feel to be a parent is very difficult to put into words. It expresses itself more as a feeling, a deep pull that originates somewhere in my biology. Which might be why, as I sit here writing this, I keep stopping, sighing, wringing out my hands, holding my breath, exhaling with a whoosh.

Realizing that I keep squeezing my right eye shut.

The most authoritarian president we’ve had in decades. The meteoric rise of tech billionaires with technocratic aspirations. Oligarchy and despotism doing battle with the liberal form of democracy, liberty, tolerance, freedom of speech and expression, and rights to privacy and self-determination that I believe in. The rise of artificial intelligence, the coming of artificial general intelligence, and the uncertainty of how exactly the rapid explosion in these fields will impact the economy, culture, and society at large. The consolidation of meatpacking plants and agricultural corporations homogenizing our food system and devastating rural communities. The insidiousness of social media, and the growing challenge in determining what’s real, what’s fake, and whether things are really as bad as they seem, or if it’s largely an illusion borne of being over-informed—and oftentimes, misinformed. Oh, yeah, and climate change (no, that little issue hasn’t gone away…).

Of all the reasons to question whether to bring a new life into this world, for me, there is one concern that rises above them all.

Is it right, is it ethical…or, to put it another way, is it cruel, to bring a child into this world knowing that there’s a fair-to-middling chance that I will pass my Chiari on to them? That through my genetic material, through my actions, I may bring a human into conscious experience, with all the pain and joy and terror and elation therein, who may develop a malformed cerebellum, which may cause them anywhere from mild discomfort, to wheelchair-bound paralysis?

This, as I mentioned earlier, was not a quandary my parents had before they had me or my sister, given they had no knowledge of Dad’s condition at the time. But what if they had had that knowledge?

If they had known about Dad’s condition, would I think it’s ethical, today, that they brought me into consciousness?

Maizy enjoying the sunset.

Some days I can recognize my positive attributes, the good things I bring to the people in my life. Due to a bad case of chronic modesty, (the kind that can cause me to feel a twinge of shame, or guilt, when I receive a compliment) I won’t state any of them here, but I do know they exist.

At the same time, there’s this other feeling. This feeling that, despite those qualities, I’m damaged goods. A lemon. A car that, from the outside, appears to be fine. That, when you get behind the wheel, take it for a spin, interact with it, nothing major seems to be wrong, other than some basic wear and tear for a car of its age and mileage.

But little do you know, there’s a crack in the frame. It’s the kind of crack that, maybe you could drive the car for another hundred-thousand miles and have little to no problems, maybe just a slight wobble once in a while that you attribute to a road that needs resurfacing.

Or, maybe one day you hit a pothole at a high speed, and this crack in the frame suddenly spreads, compromising the steering in the vehicle, and you lose all control, and you end up upside down in the ditch, or catapulting headlong into oncoming traffic, with no way to correct.

I think the risk in this second scenario is one reason I isolate as often as I do. I’m also naturally introverted, but I don’t think that necessarily accounts for the sheer amount of social and emotional connection I’ve actively avoided, or carefully held at arm’s length, over the course of my life. To have chosen paths in life that keep me alone, in a literal, physical sense, the majority of the time, even when I’m in relationship with someone. I don’t always call it self-isolation, or self-quarantine. I call it “independence” and “self-sufficiency”, when in reality my underlying fear may be that, like the defective car, anyone who is too close, too near to me, is bound to get hurt, bound to get let down in the biggest of ways when the crack in my frame eventually expresses itself in its fullest form.

This reinforces the part of me that craves seclusion, isolation, and independence, while betraying the part of me that yearns for community, family, and deep, authentic connection. And as I sit here writing this—alone in a brewery with too-loud pop-country music echoing off the walls and the concrete floor, still finding myself clenching that eye shut, still rubbing the same sore muscles in my neck, still wringing my hands out from time to time—I’m not sure I’m closer to any answers, any truths.

Or, and maybe this is a more accurate reflection of the inchoate feeling that prompted me to write this essay: I still can’t figure out what the true question is that I’m trying to ask.

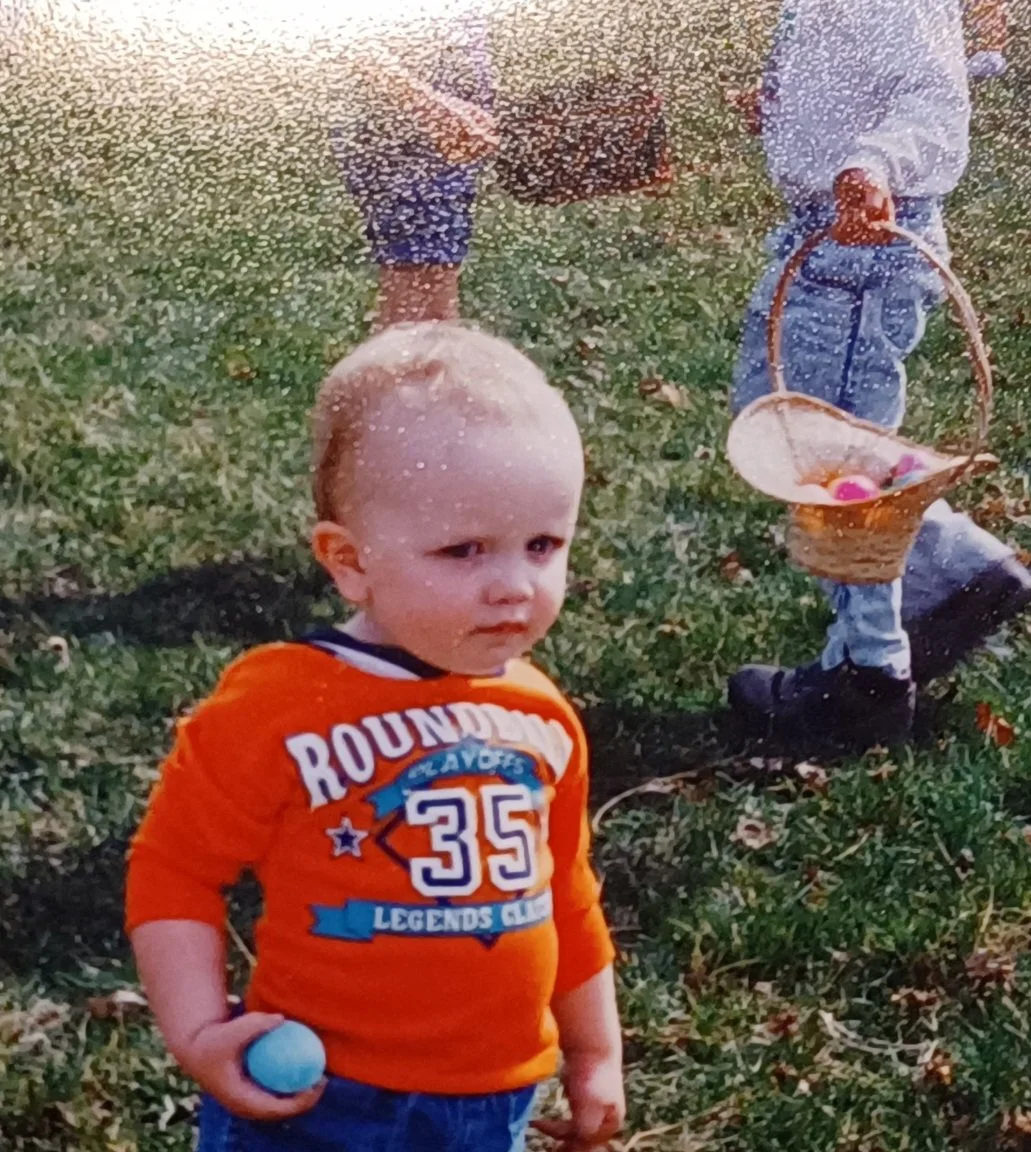

Early photo documentation of me feeling uncertainty. Probably about that Easter bunny.

As I exit the parking garage in my Jeep, leaving behind the gray Seattle skyline, a song from my country music playlist comes on. “Richard Petty”, by Billy Strings and his bandmates. Acapella, high lonesome harmonization. It’s in the bluegrass style, fairly new, but with a very old sound, which is the kind of country music I prefer. The chorus goes:

One of these days (one of these days)

I’m gonna find me a better way to live my life (to live my life)

And carry on without this strife

I know it won’t come easy but believe me when I say

I’m gonna wake up (I’m gonna wake up) and change my ways

One of these days

A lump forms in my throat, and a warmth spreads through my body as I listen, and I feel a flutter of gratitude for having a body that still does most of what I want it to do, and I take a sip of my energy drink, and I am briefly distracted from the pain in the muscles that contract themselves around the top portion of my spine, and my attention is on the song, the road, and my thoughts turn to the evening to come, of drinking hard cider around a wood-burning stove with a friend I care about like family, and I keep both eyes open, on the I-5 traffic I’m caught in, and I turn my windshield wipers to the highest setting as the road spray clouds my vision.